On June 14-15, 2025, the Japan RepRap Festival (JRRF) 2025 was held in Tokyo, Japan, drawing approximately 1,500 visitors over two days. The event featured 44 corporate booths and 59 individual booths, supported by more than 30 sponsors. What’s remarkable is that this was an individually organized event with just three months of preparation.

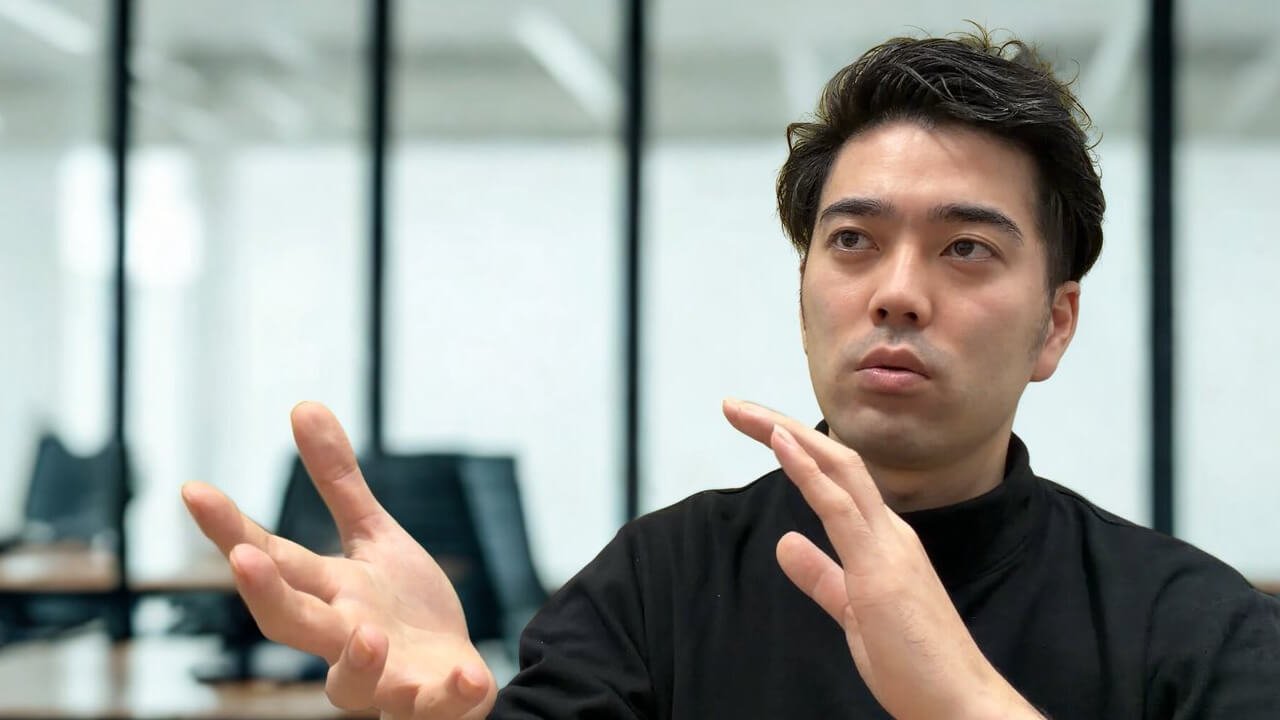

The organizer is Yuto Horiuchi, 29 years old, an ordinary office worker employed at a foreign-owned manufacturing company. He describes 3D printing as his “hobby.” Yet the scale of this “hobby” is extraordinary—he operates over 20 3D printers at home. Why did he create an event of this magnitude as an individual? Behind his efforts lies a distinctive worldview shared by the RepRap generation and critical perspectives that the industrial Additive Manufacturing (AM) industry has overlooked.

“I Did It Because I Wanted To”—The Determination of Individual Organization

Horiuchi’s motivation for launching JRRF was simple: “I did it because I wanted to.” However, beneath that simplicity lay considerable anxiety.

“Honestly, I was scared. I kept thinking, ‘What if nobody shows up?’ But I wanted to do it.”

He solidified his concept in late February, leaving just three months until the event in late May. Typically, an event of this scale requires six months to a year of preparation. Fundraising, venue booking, sponsor negotiations, exhibitor recruitment, publicity—he tackled everything alone while learning on the fly.

The risks were substantial. Venue costs alone could have amounted to several million yen. If sponsors didn’t materialize, he would have been personally liable for the debt. Nevertheless, Horiuchi pressed forward.

The results spoke for themselves: 1,500 visitors, over 30 sponsors, and more than 100 booth exhibitions. He proved that Japan’s RepRap community truly exists.

Bridging Cultures—From DIY Machines to Bambu Lab

While “RepRap” appears in JRRF’s name, the event’s character extends beyond a simple “gathering of DIY 3D printer enthusiasts.” Rather, it’s designed as a bridge between RepRap culture and modern consumer 3D printing.

RepRap refers to the “self-replicating 3D printer” open-source project initiated by Dr. Adrian Bowyer in the UK in 2005. Its philosophy aimed to democratize knowledge and tools, creating a world where anyone could freely improve and share. Horiuchi grew up within this culture.

However, Horiuchi deliberately avoided making it “an event exclusively for hardcore DIY machine enthusiasts.” He welcomed users of commercial products like Bambu Lab and Creality, who indeed attended in large numbers. Survey results showed Bambu Lab and Creality ranking among the top machines used, while DIY machines (Voron, Ratrig, etc.) maintained strong popularity. Horiuchi intentionally targeted a broad audience, including newcomers, rather than limiting it to “hardcore DIY 3D printer enthusiasts only.”

“I’m not really obsessed with DIY machines. First, I want people to enjoy the world of 3D printing. If they become interested in DIY machines from there, that’s great. Even just knowing about them is enough.”

Symbolic of this approach was making admission free for children. “I wanted the next generation to see it for free.” This represents an investment in 10, 20 years ahead.

Consumer Manufacturers Creating Movements

JRRF 2025 wasn’t made possible by Horiuchi’s individual efforts alone. Behind it lies the “movement” that consumer 3D printer manufacturers have built.

Bambu Lab’s rise is emblematic. Since entering the market in 2022, it has generated explosive discussion centered on X (formerly Twitter), creating a massive influx of “people newly entering 3D printing or returning because of it.” JRRF’s survey showed X (Twitter) as the overwhelming top choice for information gathering (estimated over 70%), followed by word of mouth.

“Japan has the world’s second-largest number of active users after the US. Focusing on X (Twitter) is a good choice for companies struggling with marketing,” Horiuchi points out.

Prusa Research founder Josef Prusa himself comes from the RepRap community and hosts Prusa Fest in the Czech Republic annually. Creality democratized the market with the low-cost Ender 3 and has tolerated and encouraged modification culture. These manufacturers have adopted strategies of “building communities” before “selling products.”

In contrast, many industrial AM manufacturers distribute ROI calculators and tout “productivity improvements” and “cost reduction.” They disseminate information on LinkedIn, which barely functions in Japan. Their communication is predominantly manufacturer-driven and one-directional, with limited user community cultivation, failure case sharing, or open discussion forums.

Are “non-disclosure agreements” and “it’s industrial equipment” truly barriers? Or are they excuses to avoid community engagement?

The Disconnect Between the World Young Generations See and Industrial AM

JRRF’s visitor demographics are intriguing. Survey respondents were most commonly “office workers.” While it’s a hobby event, many attendees work in manufacturing. In other words, they’re also potential B2B customers.

Even more significant is the presence of young people, including elementary and middle school students. At the venue, children earnestly studied DIY 3D printer mechanisms, asking questions like “Why is this part necessary?” While Japan’s Ministry of Education promotes STEAM education, JRRF served as a venue for “living technical education” that transcends textbook learning.

However, Horiuchi harbors concerns. “There’s a severe shortage of personnel capable of teaching STEAM education. Most school teachers have never used programming, 3D CAD, or 3D printers.” Mechanisms for appropriately transmitting the knowledge and experience of the enthusiast community to educational settings remain unestablished.

Who will be implementing and operating industrial AM in 10, 20 years? Won’t it be the young generation now attending JRRF? They’re growing up in a culture of gathering information on X (Twitter), sharing failures, and learning through communities. Is the industrial AM industry prepared to understand the world this generation sees?

The Future the RepRap Generation Sees

In late September 2025, Horiuchi participated in 3DPrintopia (formerly the East Coast RepRap Festival) held in the United States, sharing JRRF’s experience. Overseas X accounts have been discussing the RepRap event held in Japan. He’s acting as a member of the international RepRap community.

JRRF 2026 is being considered for May 30-31, 2026. Even in selecting a venue, Horiuchi prioritizes locations where “exhibitors can transport items by car” and that are “wallet-friendly.” Large facilities like Tokyo Big Sight are “still premature.” He puts the community’s sustainability first.

“Perhaps there should be a Japanese version of AMUG,” Horiuchi suggests. AMUG (Additive Manufacturing Users Group) is a user-led event held annually in the US under the banner “For Users, By Users.” Deep discussions about advanced industrial AM applications occur across corporate boundaries.

What Horiuchi sees “beyond” may not yet be fully articulated even by himself. However, what his actions demonstrate is clear:

Culture over Commerce

Community over Corporation

Access over Profit

Future over Present

The future of 3D printing that the RepRap generation sees isn’t just about ROI or productivity improvements. It’s a world where knowledge is democratized, failures are shared, and the next generation can learn freely. For the industrial AM industry to truly grow, perhaps it needs the resolve to understand the future this generation sees and walk alongside them.